|

Editorial Directory

|

|

|

Editorial Home

|

|

|

|

|

Reef

|

|

|

|

Cave

|

|

|

|

Wreck

|

|

|

|

Photo/Video

|

|

|

|

Equipment

|

|

|

|

Expedition

|

|

|

|

Dive Med

|

|

|

|

Other Editorial

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

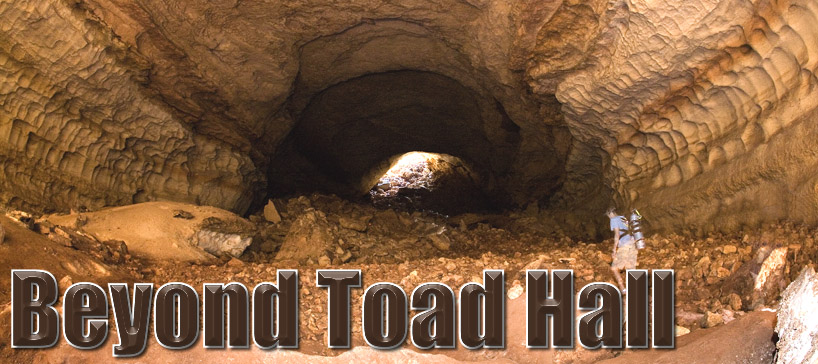

In Sept 1982 three Australian Cave divers surfaced after an almost 4km underwater swim in Cocklebiddy cave to discover a huge underground lake and a series of dry rock chambers the likes of which had never been seen in Australia. This chamber was ten meters high and two hundred and fifty meters long; they named their new discovery ‘Toad Hall’. Back in 1982 a world record was set for the longest submerged cave passage in the world. Despite the fact that this record has long since surpassed with the discovery of longer underwater systems around the world, a swim to ‘Toad Hall’ is still regarded a long distance cave penetration.

As Hugh Morrison, Ron Allum & Peter Rogers did twenty seven years before me, I too emerged into ‘Toad Hall’ after what can only be described as a spectacular underwater journey through an amazingly formed underwater cave. As excited as I was to have travelled this distance underwater in the cave dive I was equally excited to find out why this place was called ‘Toad Hall’! As I surfaced into ‘Toad Hall’ so too did my dive partner Agnes Milowka, a young diver from Adelaide who was born the year before ‘Toad Hall’ was discovered!

Eager to remove her dive equipment as I was, we both scrambled out of the water and climbed into the dry chambers of ‘Toad Hall’ to be confronted by a hard plastic slate bearing many names. Over the 27 years that is had been here, those who had made the journey have the honour of adding their name to a list of what can only be described as the who’s who of cave explorers in the southern hemisphere. Before this expedition less than fifty people including one female had added their name to the list of honours! We added our own names and despite the high levels of C02 moved on to explore ‘Toad Hall’ for ourselves.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Veteran cave diver Ken Smith prepares to leave the lake inside Cocklebiddy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Craig Challen prepares for a long dive to the end of the cave |

|

|

|

At the far end of the ‘Toad Hall’ chambers the cave once again breaks down and in typical Cocklebiddy fashion a pile of rocks leads down to yet another sump (submerged passage) for the caves continuation. It was here that three days later Agnes would once again don her equipment to dive almost the entire swimmable length of the sump to claim an Australian record for the furthest underwater cave penetration by a female diver. After exploring ‘Toad Hall’ we spent another two hours photographing the various chambers before preparing for our journey back. After even more photography on the way back and a round trip of almost 8km, most of which was underwater, we arrived back at the entrance lake and finally emerged from the cave fourteen hours later. Despite a small scooter malfunction which meant Agnes had to physically swim 2.5km of it! Nothing however, that she hadn’t done before! So she said!

This expedition was a full frontal assault on the cave using the very latest technology available to divers and underwater explorers. It was also an extension of the previous years attempts by the same team to find the physical upstream end of this submerged cave. Our small photography trip into ‘Toad Hall’ felt insignificant in comparison to the full on attacks planned for sump three and beyond ‘Toad Hall’, all of which was being set up around us. The lead divers on this expedition were Australians Dr Craig Challen, Dr Richard Harris & Rick Stanton, who alongside me, had travelled all the way from the UK. A highly experienced team of divers would support the expedition and each man in his attempt to explore the physical end of the cave system. The key to this expedition, and ultimately the success, would be the closed circuit rebreathers and long-range diver propulsion vehicles (DPV’s) utilising the very latest lithium battery technology.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rick Stanton as he leaves for a long dive into the cave |

|

|

|

|

|

The Nullarbor

As the divers make their way underwater to the furthest reaches of Cocklebiddy Cave above them is the diver’s camp in the heat of the vast Nullarbor Plain desert. The Nullarbor is the world's largest single piece of limestone, and occupies an area of about 200,000 km. At its widest point, it stretches about 1,200 km from east to west between South Australia (SA) and Western Australia (WA). The prevailing climate across the Nullarbor is typical of a desert, characterised by arid to semi-arid conditions, with maximum daytime temperatures of up to 48.5 °C (119.3 °F). At night, well that’s a different story, and with it brings freezing conditions and creatures that you can only wonder where they actually live by day! Although the Nullarbor is flat and featureless it is home to thousands of Kangaroos and of course the odd deadly spider so keeping your tent protected is a high priority. Being the largest single piece of limestone in the world also makes the Nullabour a Mecca for cavers who travel long distances to camp out and explore the regions many caves. We were here though, specifically to explore one cave, Cocklebiddy, which offers the greatest underwater penetration of any cave in Australia.

This expedition comprised of fourteen divers who all arrived at the cave on 24th March soon after the Oztek technical diving conference in Sydney and having travelled from different sides of Australia. The overall plan was to set up the camp directly outside the cave entrance, which would then act as a base for all operations. Large generators towed out to the Nullarbor would power the camp and the powerful lighting that was run into the cave to illuminate the lake where diving operations began.

On the Nullabour there are no showers, no toilets and no water! Everything had to be brought in. This was a true expedition in the very word of exploration. Tons of diving equipment brought into the desert would then be lowered into the cave using an ‘A’ frame and then physically being carried the remainder of the way down to a huge underground lake that marks the start of diving operations. From the camp above the cave it is 90m vertically to the underground lake with approx 200m of literally heaving all of the equipment down a boulder pile in the dark. Once the diving equipment was all at the lake, deep underground, the plan then was to set up the dives. Safety cylinders would be dropped strategically along the cave in sump two in ready for the big dives as well as transporting all necessary equipment required for dives beyond ‘Toad Hall’ to the far side of Toad Hall itself. This would take several days before the big dives began to take place, then we would have to clean the cave out in reverse.

|

|

|

|

| Above: Craig Challen prepares for a long dive to the end of the cave |

|

| Above: Agnes Milowka adds her name to the Toad Hall visitors slate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cocklebiddy is regarded as the Mount Everest of cave dives in the southern hemisphere and only a handful of experienced and trained cave divers venture into the magnificent sump two. The cave is broken down into three dives; sump one which is 1.2km in length and runs from the lake to a rock pile air chamber. The diver then has to take all of their equipment off and carry it over a 100m of collapsed rocks before descending down the rocks again to sump two. The spectacular sump two is 2.5km in length before it arrives at ‘Toad Hall’ where the diver once again removes all of their equipment and carry’s it over to sump three, a distance through varying chambers of 220m. Sump three is approx 1.7km in explored distance of which 1.2km is reasonably large and easy going before it closes down a lot smaller but still large enough to swim through with back mounted diving equipment. The diver then gets to approx 1.5km into the sump where the passage then becomes to small and tight to swim with a back mounted system. From here the way on becomes a side mount equipment dive then only after approx another 100m or so the passage becomes even smaller, enough for the size of a diver to fit in and hence a ‘No Mount’ dive i.e. the divers has to push whatever it is he or she is breathing from in front of them! Of course if you are at this point the likelihood is that after a distance of 5.7km into the cave you’re not using conventional scuba. The push divers on this expedition were using a variation of their own home made rebreather configurations, which run in considerably smaller in size than a standard manufactured unit. These where transported to the far end of the cave before being used for the final pushes. |

|

|

|

|

|

Diver Mick Green scooters into sump one |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mark Brown pauses before heading into the caves depths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leigh Bishop prepares his scooter deep inside the cave (Photo Jeff Paynter) |

|

|

|

First Dives

The very first dive in Cocklebiddy was back in 1961 although due to lack of available equipment the divers were unable to penetrate any distance into the newly discovered submerged tunnel. The first serious dives began in the early 1970’s where several hundred of meters of line were then laid. By the mid 1970’s a joint South Australian team pushed the cave distance to 1.5 km to discover the first air chamber, commonly known as the ‘Rock Pile’. This was basically a long lake with a 20m high and 80m long pile of rocks. Beyond this the divers discovered the cave continued, again with a second submerged passage, sump two.

During the mid to late 1970’s almost every year with the exception of 1978 saw a full on expedition to make further dives into sump two with the aim of surfacing into yet another exciting air chamber. As the submerged passage grew longer the divers utilized the technique of pushing underwater sleds of multiple cylinders that they could breath from. In 1983 a year after ‘Toad Hall’ was discovered a five person team of French cave explorers headed by brothers Frances and Eric Le Guen set a new world record for underwater penetration. Eric Le Guen did the first dive and managed a 1460m penetration into the third sump from Toad Hall. His brother Frances, on a later dive, then managed to push the cave another 90m by squeezing through a restriction but was stopped by a second restriction too tight for him to pass with his back mounted diving cylinders. A total of 1550m of line were laid in the third sump. After their second dive, the brothers broke the entrance lake surface of the first sump 47 hours after their initial departure. Soon after the French left, and in typical style, Australian divers took back what was rightly theirs and numerous leading edge divers have since pushed sump three to as far as it is today.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Divers at the lake pool ready to begin their dives |

|

|

|

|

Rebreather Technology Arrives

The latest man to take up the challenge of exploring the far reaches of the cave is Perth based Australian diver Dr Craig Challen. In 2008 Challen reached a new point after laying an additional 100m of line beyond his predecessor Chris Brown. Challen found himself in very low bedding plain, against the flow of water and in little, if any visibility. Forced to retreat due to low gas levels he has returned back to see if he can push on further past his 2008 point. With him to also challenge the far reaches is Dr Richard Harris, an Adelaide based technical diver who holds the record for the deepest dive in Australia and New Zealand. After both men have had their attempt well known cave diver Rick Stanton from the UK will make his inspection at the far end. Each of these explorers will make a separate attempt on different days; the nature of the cave suggests there is only room down there for one man at a time!

Until now, no one, before these men have been able to reach this far in the cave and what these men share in common is the fact that they have now introduced rebreather technology to Cocklebiddy. This technology allows the divers to recycle the gas quantities carried in order to reach the far ends of the cave. Another team member Melbourne based John Dalla-Zuanna has developed the very latest in lithium battery technology inside the DPV’s which will transport the men to the far reaches of the cave and back without swimming the entire 11.5km underwater journey.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Author Leigh Bishop in sump 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The entrance to the cave where all the equipment is lower into |

|

|

|

|

Cocklebiddy Geology

Looking at the entrance to Cocklebiddy it’s obvious to see that this cave as with many of the caves on the Nullabour is nothing but a surface collapse at one point in the caves length. Basically the cave created below, at some point in time, became too large to support the rock that remained above and hence collapsed in on it self, opening up the cave as we know it now. There is a theory that there is a southern passage, but no one has yet found a way into it, therefore the explorers of today concentrate on exploration upstream. The cave was formed some ten million years ago and it’s only due to the fact that at one point in its length a collapse occurred that we are aware of its existence. Quite possibly there are other caves under the Nullabour that are even bigger than Cocklebiddy that we are just unaware of because they simply have not collapsed.

The current theory for these caves formation is that fresh water from rainfall permeates the limestone and meets the existing saline groundwater. The mixing of these waters causes a corrosive action and dissolves the limestone, thus creating a horizontal cave system at this depth.

The result of this here in Cocklebiddy and especially within sump two is an underground passage to take your breath away on a world scale. Although he had to think about it over night, the following day after his first dive in sump two, Rick Stanton, veteran of cave dives around the world, declared sump two the best sump he had ever dived in. The passage is unlike the other two in that it is extraordinarily large, large enough in fact to drive two double Decker buses down side by side.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rick Stanton as he leaves for a long dive into the cave |

|

|

|

As it takes on a winding effect a divers DPV transports them through a beautifully decorated passage of calcite and white flowstone in what can only be described as crystal clear visibility! The more powerful your torch the more amazing your experience will be! This was certainly one of the best dives I’ve ever made in my life, and looking back now, with the treasured memory still in my mind, it makes me even think if it was real or not!

The end of the cave

Unfortunately for both Challen and Harris equipment problems meant that they were unable to reach the end of Challen’s line laid in 2008. As disappointed as they were they would wait for the word of Rick Stanton after he had made his attempt of just how much further a diver can explore. On the surface the progress of each exploration divers was being monitored using radiolocation pingers, which also helps to map the cave system. Below surface my plan was to see Rick safely off from the lake and later that night meet him at the ‘Rock Pile’ between sump one and two. From the rock pile I was able to radio the surface and let the camp above know Rick was back safe, which was of course, when he arrived. Ric acknowledged Agnes Milowka in passing in sump three just before the waiting room then eventually reaching the end of Craig Challen’s line Rick tied his own line off to the end of it before progressing only a few meters. Here the cave takes on the nature of wide bedding plane possibly 20-30m wide, only big enough for a diver to navigate by passing through rock erosion features and channels in the floor. Rick had little if anything to belay his line to and found the going elbow deep in mud with zero visibility. As this is a percolation cave it appears that the point reached by Challen in 2008 could well be the source of the water intake. Rick reeled in the few metres of line he ran out and retreated claiming no more passage to be found and that Challen had officially got to the most remote part of the cave the year before. Quite possibly more progress could be made but at this point in the cave there is little possibility of it opening up again and it will certainly become too small for a human to progress not far beyond. Agnes Milowka and Ken Smith were back at Toad Hall to video Ric's comments on his push dive before exiting themselves and bringing with them a haul of cylinders which began the big ‘after push’ clean up.

I had waited in darkness at the ‘Rock Pile’ for Rick for five hours providing radio updates on the hour to the surface. As a storm was passing through the camp above the powerful lights of Rick’s torches arrived at the ‘Rock Pile’ and I helped him with his heavy equipment over the rocks to sump one. Rick explained to me what he had seen as well as his theory on the geology of the furthest reaches of the cave before we both dived out a few hours after my last update to the camp above. Our expedition was over; we had taken eleven people to Toad Hall, the most people of any previous expedition as well as putting the first two female divers into sump three; one of whom set an all new distance record for an underwater Australian cave. We also now have a clearer understanding of the Cocklebiddy geology beyond ‘Toad Hall’. The naming of ‘Toad Hall’, even today, is a secret kept by those who have ventured there, as the saying goes, ‘Many will wonder, but few will know’!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Author Leigh Bishop in sump 1 with a large scooter and death ray light |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Craig Challen prepares to leave Toad Hall and dive into sump 3 |

|

|

|

The Cocklebiddy expedition team were, Dr Craig Challen & Dr Richard Harris (expedition leaders) Ken Smith, Geoff Paynter, Leigh Bishop, John Dalla-Zuanna, Rick Stanton, Doug Friday, Mark Brown, Mick Green, Agnes Milowka, David Bardi, Sandy Varin & Jamie Brisbane.

To dive in Cocklebiddy cave all divers have to be penetration qualified cave divers and permits to dive at the cave are required through the CDAA (Cave divers association of Australia) www.cavedivers.com.au

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Melbourne diver Agnes Milowka after

setting a new female distance record |

Mark Brown aka ‘Wiz’ with some of

the 250m of air line that led down into

the cave to fill cylinders |

Support diver Geoff Paynter carry’s

equipment into the cave |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|