|

| |

|

|

|

| Text by Harvey Schmiedeke

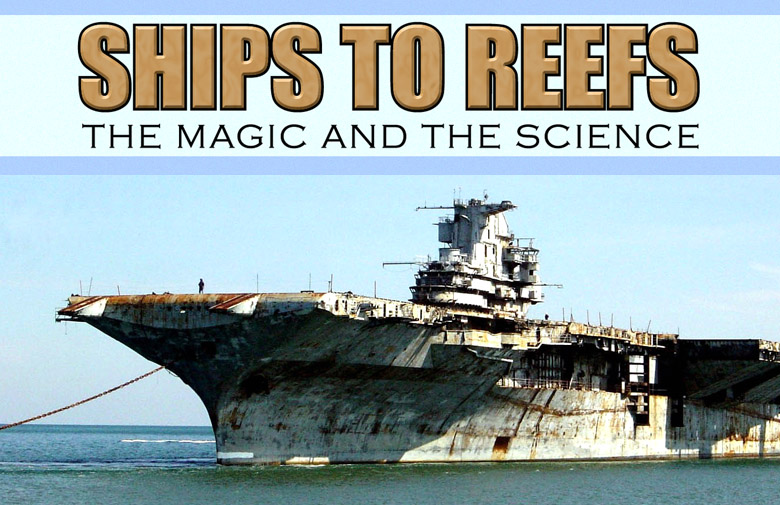

Whether it’s the little tug boat reefed in 25 feet of water in Curacao or a newly discovered German U-Boat being explored by a tech team, the allure of sunken ships is irresistible.

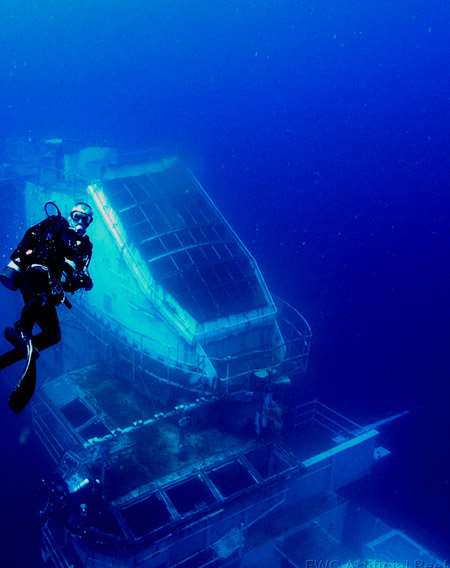

On a shallow wreck frequented by cruise ship snuba divers in Carlisle Bay, Barbados, I once found a full set of dentures. No doubt some rapturous geezer ran out of hose trying to get as close as possible. Earlier that day and just a few miles away I penetrated the Greek freighter Stavronokita forward of the propeller. I then had my own “religious experience” working my way up, deck by deck, videoing the amazing interplay of light, life and forms, eventually to deco on the mast— a psychedelic forest of invertebrates and fish.

Let me ask you a couple of questions.

If you’ve been diving for decades, what do you notice about the changing conditions under that choppy surface? Depleted fish and invertebrate resources, damaged and bleached coral, invasive species and pollution are a few of the “crimes” to which we as divers are eye witnesses.

On the other hand, if you’ve been diving any of the growing number of ships intentionally sunk as man-made reefs—from the Spiegel Grove in Florida, or the Yukon in California, or the McKenzie in British Columbia, what have you witnessed? Over a period of ten years or less, these ships begin resembling parade floats through an incredible explosion of life. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here on the left coast, and to the North, white plumose anemones, sea fans, and even kelp become home for all sorts of critters. On the east coast and to the south, sponges of all varieties spring up along with fans and invertebrate life. The reef becomes home to a density of critters that can, literally, make your head spin.

Leave a ship open to the elements on the surface and it just rusts and becomes a toxic mess. Have you ever wondered how it is that the living ocean transforms ships with the enthusiasm of a child creating a “castle” from a large cardboard box?

The simple “science” of reefing is really nature’s way of recycling. Put a ship (or any object with a positive electrical charge) in the ocean (seawater has a negative charge) and the magic happens. That smidgen of current instantly begins encapsulating the ship with calcium carbonate and creating a fertile field for those trillions of little critters like plankton that float eternally in the abyss looking for a place to call home. What was once a home for sailors now becomes a home for marine life.

I refer to such intentional sinkings and the reefs that result as either cultured reefs or man-made reefs rather than “artificial.” There is nothing artificial about them.

The attraction of these sunken treasures is not only to our marine brethren of course. Divers flock to these ships, spending money and stimulating enormous economic benefits.

THE ECONOMICS OF REEFING

There are really only four ways to recycle the many hundreds of ocean-going vessels that are retired annually on Earth.

First, you can scrap them for razor blades or rebar, here in the US or overseas. Until recently, steel prices have been so low as to make this a losing proposition for scrappers. There aren’t any scrappers on the West Coast, for instance. Rising steel prices have made this more attractive, but the economic benefits are short lived and not as sustainable as ships to reefs.

That’s the case with domestic recycling. Ship breaking overseas such as that in Alang, India is such a human and ecological disaster that Greenpeace set off an international firestorm a few years back, and rightly so. In the US, this alternative for scrapping Navy ships is banned, though some ships with home ports in Caribbean countries and elsewhere still participate.

Secondly, you can clean the ships and use them for sink exercises in the deep ocean, which has zero economic upside other than disposing of the problem quickly and giving sailors target practice. The downside is that the ships still have to be cleaned, though not to the standards they are for reefing and thus there are possible toxins and spread of invasive species.

The third alternative, and what the government has done which has resulted in a PR and legal nightmare for them in Suisun Bay, is to warehouse the ships for decades. Uncleaned, exposed to the elements, |

|

|

|

|

| the deteriorating ships become a toxic time bomb. Economically, the cost for mere storage has risen to billions over the years. This is not a solution at all. It is the avoidance of a solution and it’s come back to bite them in the butt with a lawsuit from Arc Ecology 2007.

The fourth and only truly sustainable alternative, with benefits for both the ecology and the economy, is to clean the ships of all toxic substances and to strategically sink them as man-made reefs. Many sinkings are within recreational diving depths, though some (like aircraft carriers) can be sunk in deep waters.

Pioneering provinces like British Columbia and countries like New Zealand attract millions annually and states like Florida with just under 2400 artificial reefs realize billions of dollars in underwater tourism. This is all to the benefit not only of the dive community, but to economic interests like transportation, tourism, hotels and restaurants.

The government, sitting atop this economic chain, benefits through increased tax revenues. Tax consumers become tax payers.

All good, eh? You may well ask, as many of us have, what’s the “down side” to reefing ships? Why is it that this process isn’t embraced by everyone? Why do some even oppose it?

THE POLITICS OF REEFING

My daughter was watching an episode of The Simpson’s recently when I passed through the living room. Homer, asked to participate in a community project, paused to worry over the proposition, then asked, “Do I have to do anything?”

We’re going to discuss the current impasse with getting retired naval ships under reasonable terms from the Federal government, but before we shift blame to the Feds, let’s not be Homer Simpson.

The downside is that somebody, driven by purpose and willing to put their butt on the line, has to do it. “Doh!”

It seems for every one person willing to actually do something, there are at lest 283 bureaucrats and nay-sayers determined that you’re not going to do something, and about 2,830,000 among even those who stand to benefit from reefing, that are caught in the “Homer effect.”

The interview that follows is a study in such purpose and tenacity. Anyone crazed enough to put the boots on to begin the journey to reefing and those who hope to benefit from this movement will do well to listen to his words.

I first met Dick, like many divers do, through his products. My CLX 450 dry suit became a constant companion, followed by a CF 200 model. You build a certain affinity for the man through the quality of his products and the many adventures they make possible, even without meeting him.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But, one day four years ago, I saw an announcement for a Ships to Reefs meeting in San Diego and made my way down from LA to a meeting which had attracted about 50 others.

Frankly, there was a lot of enthusiasm and noise in that room, desire and confusion, opinions and disagreements—a lot more heat than light.

And then Dick took the floor.

When Dick speaks people listen and things can settle down. Not because he’s such a “calming influence”; he is very direct and expects the best from those who work with him. I personally appreciate it and am likeminded. The reason people listen is because it becomes apparent that the man has forgotten more about ships to reefs than the rest of us—collectively—will probably ever know.

Ships to Reefs are the future of diving.

Whether you embrace the movement for its ecological benefits and to take pressure off of natural reefs, or for the enormous economic benefits it holds, do something.

Whether you want to put the boots on and lead or take the journey as crew, jump on board.

Whether you are in the dive industry and stand to make a more prosperous future for the profession, or you are a diver who simply wants to explore the

sunken treasures when the job’s done,

work with us.

https://www.cs2r.org/

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|