|

| |

|

|

Text by Richard Harris

Photography by Gary Barclay, Ken Smith, Peter Horne, and Richard Harris

In the extensive swamplands of the Piccaninnie Ponds Conservation Park, lies a freshwater marvel unlike any other in Australia; Piccaninnie Blue Lake, affectionately called “Pics”. A truly unique feature even compared with the numerous other stunning sinkholes of the Mount Gambier karst region of South Australia. Every year thousands visit the ponds to snorkel in, dive into or simply gaze upon the waters there.

And probably every visitor has shared the same thought; what lies in the deep section of the cave beyond the limits of recreational diving? Richard Harris revisits the history of this site and reveals some amazing new discoveries down deep…

“Pics” has captured the imagination of divers and scientists alike for decades and has been featured in many magazine articles and television specials. Iconic images of cave diving in this country will usually include a diver in the spectacular Chasm or Cathedral section. Ron and Valerie Taylor filmed Pics in their 1966 classic “The Cave Divers”. Famous underwater photographer David Doubilet captured its beauty for National Geographic in 1984. But less well known is that divers from the Sub Aqua Speleological Society of Victoria (SASSV) including Ron Addison, Lorraine Newman and Elery Hamilton-Smith reportedly dived it in 1961 after it was discovered by eel fishermen. Local divers “Snow” Raggatt and “Mick” Potter were diving the site by 1962 and what an awesome experience it must have been for all these pioneers when they first bush-bashed out into the swamp through the fierce cutting grass to snorkel across the First Pond. Suddenly beneath them, as the reed curtain parted, the floor would have dropped away and the seemingly bottomless Chasm was revealed for the first time! Even today new visitors to the Chasm may be overcome with a sense of vertigo as the floor disappears! Back then the waters would have been bursting with life; aquatic plants, fish, turtles and water birds as well as less visible invertebrates. Pics was and still is, truly an oasis in the middle of the swamp.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above: Chris Edwards floats on the surface as he prepares to dive.

Left: Crystal clear waters and filtered sunlight make the shallow parts of the Chasm a photographer’s playground. Liz Rogers kindly poses for the author.

Below: Dean Chamberlain, one of the deep rebreather divers uses the new Optima from Dive Rite. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

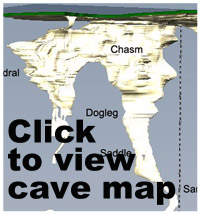

Peter Horne (one of Australia’s best known cave divers and field researchers) once described the ponds as follows: “The lake consists basically of an oval-shaped pond oriented roughly northwest to southeast some 30 metres in diameter, connected to which is a 40m long straight water-filled rift which runs almost exactly east to west, from the western edge of the large pond. The oval-shaped pond, called the First Pond, is only 10m deep and shaped like a bowl, but the Chasm to the west drops vertically to 30m, where it constricts to a near-vertical, 10m-wide tube called the Dog Leg, which continues to depths far beyond 60 metres. The Chasm continues underground at its western end for about 20m more, in an awe- inspiring cavern called the Cathedral, which drops to a depth in excess of 40m”.

Peter and his team were perhaps the first to really appreciate the main features of the system, mapping the complex with considerable accuracy to a depth of over 40m in the mid eighties. Even then Horne was struck by the unusual nature of the cave, unlike any others in the area. Classic Mt Gambier sinkholes are true “cenotes”; bell shaped holes formed by the dissolution of the underlying limestone, which continues until the ceiling collapses under its own weight forming a window into the aquifer. These can be enormous and deep like The Shaft and Kilsbys Sinkhole. But Pics is different, showing little in common with these sinkholes. Furthermore, the Ponds are clearly influenced by their close proximity to the coast. The water is slightly brackish and is flowing up from somewhere deep inside the cave, and then out to sea through a small creek. The complex biodiversity of Piccaninnie Ponds compared the other sinkholes also reflects its marine influence. The 1985 mapping team’s efforts clearly highlighted the possibilities for further exploration at the bottom of the Cathedral and the Chasm.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Right: Grant Pearce in the Cathedral, well named for the ethereal light that filters into this beautiful part of the spring system.

Below: Grant Pearce is the scientific coordinator of the study and an accomplished rebreather diver. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But as the 4 fatalities that occurred in the Ponds between 1972 and 1984 demonstrated, cave diving techniques and equipment were still in a state of development, and deeper exploration was not yet a sensible option. In fact the National Parks and Wildlife Service (in conjunction with the Cave Divers Association of Australia) introduced a maximum dive limit of 36.5m. The two 1984 fatalities occurred after a dive to 68m in a constricted silty passage in profoundly narcotized divers.

Fast forward to 2004. Like most divers who visit the Ponds I wanted to explore the deeper sections to see what lay beneath. There was no doubt that clandestine, illegal deep dives had occurred over previous years and horizontal passageway at depths of around 100m had been rumoured. But I also heard of some frightening near misses during these dives. I decided I was going to do it properly or not at all. Not surprisingly my initial enquiries to the CDAA and the Department of Environment and Heritage (DEH) were met with some skepticism, as I am sure many similar overtures had been made and rejected before mine! Clearly an exploration-based mission to simply plumb the depths was not going to be acceptable. So I went on a fact-finding mission, learning as much as I could about the local geology, hydrology and biology. Soon my quest for the bottom was replaced by a genuine passion to unravel some of the mysteries of this unique place. Where was the water coming from? Would one discover a lens of seawater mixing with the fresh spring water at depth? Would the answers regarding the unique genesis of the site be discovered below the Chasm?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Liz Rogers diving in the Cathedral, one of Australia’s most beautiful cave diving sites.

Below: Grant Pearce collects water samples near the shallow data logger. These samples are used to calibrate and ensure the accuracy of the information. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

So I re-approached the CDAA and the landowners with a more formal proposal containing both science and exploration. Several pieces of good fortune came together to give the project the green light, and mostly it was down to good timing. In 2006 the National Water Initiative meant that water was now a political hot potato. Funding for groundwater research was becoming available and scientists at the DEH were very interested in unraveling the mysteries of the “groundwater dependent ecosystem” in Pics. Secondly, local landowners were becoming more familiar and accepting of newer technologies such as mixed gas diving and closed circuit rebreathers, which made deep exploration safer. Since I had been very active in this area in recent years, all the stars lined up and we were given the green light. The Piccaninnie Ponds Collaborative Research project got underway soon after.

Grant Pearce; the Southeast Manager for Groundwater Science with the DWLBC, is also a local cave diver. He headed up the scientific side of the project with the following major goals:

1) To install water analysis equipment in the cave to help understand the local hydrology.

2) To explore and survey the system below the current map limit (40m).

3) To video and photograph the cave for the purposes of geological assessment.

The first project dives commenced in May 2008 with a small group of rebreather dives to the deep sections of the Chasm. John Dalla-Zuanna (“JDZ”) and the author gradually probed the depths over several days until the first extraordinary discoveries were made beneath the Dog Leg. The author’s notes reveal the details of that memorable dive: “JDZ and I dived in the Chasm again and quickly followed the line to the top of the fissure at 74m. I dropped feet first through the tight fissure (JDZ stopped there as safety diver) to the old white line and followed it down to 90m noting a horizontal passage approximately 15m long heading west towards the Cathedral side of the system. At 90m the white line ended in a tie-off on the eastern wall. No other line was found in this area, so after tying off a new line I pushed down and to the west slightly until at a depth of 105 metres the floor came into view, containing several holes roughly 2 x 1m across. I dropped into the last of these, but the very friable chalky silt quickly enveloped me and all visibility was lost. The soft silt floor was at a maximum depth of 110m.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Right: “JDZ” explores the extreme depths, searching for extended passages. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rising above the silt, I then noticed that any further exploration to the west appeared to be blocked by a large boulder. However as I ascended I realised that there was a passable gap between the top of the boulder (now called "Sentinel Rock") and the ceiling of the “Subway Station” room. Swimming over the top at a depth of 96 metres, I entered clear water again and the gap between floor and ceiling increased. Suddenly, I found myself ...staring into space, my light barely illuminating the opposite wall of a large chamber! For me, this was a once-in-a-lifetime moment. Pure joy as all the work of establishing the project was rewarded, with interest! (The "Chamber of Secrets").

Nearly at turn time so I reeled out approximately 30m across the chamber, intermittently tying off on the silty floor boulders. The chamber curved to the right before slowly narrowing and ending in a sheer wall. The maximum depth at the end of the chamber was 107m, and several promising leads were noted around the perimeter. At exactly 30 minutes I made my final tie-off and swam out of the cave, surveying the line on the way out. In places, fossil scallop shells were noted embedded along the walls, and what looked like large "yabbie" tracks (?Cherax sp.) were also noted in the floor silt. There were no signs that anyone had ever visited this area of the cave previously. Total dive time about four and a half hours.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above: “JDZ” places a Pinger at 107m depth then turns for home.

Below: Grant Pearce decompressing after a deep exploration dive.

|

|

Following this discovery, numerous dives were spent surveying and videoing the new finds. Ken Smith’s radiolocation “pingers” were used to mark the limits of the Chamber of Secrets in order to reference it to the shallow system, and JDZ produced a stunning 3D computer generated map of the finds. Since then many dives have been performed in different parts of Piccaninnie Ponds by a large number of team members. Water chemistry sensors have been placed in 3 areas including the deep section, which will produce vast amounts of data for the hydrogeologists. Water, rock and sediment sampling as well as analysis of video by geomorphologist Ian Lewis is giving new insights into the formation of the ponds including the possibility that ancient volcanic activity may have played a role. Each research dive reveals new scientific information and adds areas of the cave system to the map.

Most importantly the multiple exploration dives below 100m depth on mixed gas rebreathers have been conducted safely. Deep technical cave diving carries a small but real risk, and it is a credit to the CDAA’s training proficiency and to the professionalism of all the divers that the project has been conducted without any significant incident.

The mysterious waters of Piccaninnie Ponds are slowly revealing their secrets and research is ongoing. Eventually we hope to have answers to all our questions about this remarkable place.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to take this opportunity to thank Steve Bourne and the DEH, Grant Pearce, Peter Alexander and the DWLBC, and the directorate of the CDAA for their assistance with the project thus far. Our thanks also to all of the divers involved and the technical staff who have donated their time and energy to assist with the safe conduct of the project. Finally to Sea Optics Adelaide, for their ongoing support. The DEH would like to remind all divers that the current depth limit of 36.5m still applies to suitably qualified divers visiting the Ponds.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Richard Harris the project coordinator, about to submerge with his Mk15.5 closed circuit rebreather. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|