|

| |

|

| |

Editorial by Chris Borgen and Dan Warter

Photos by Chris Borgen |

| |

|

|

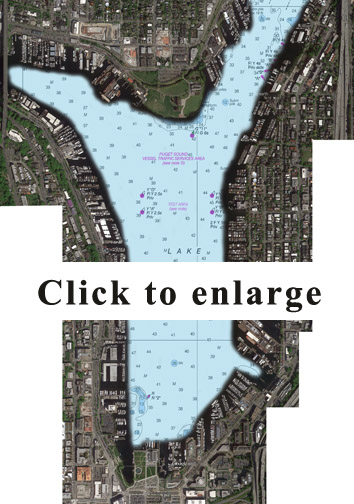

Lake Union is a bustling waterway located in the heart of downtown Seattle, a large metropolitan area that is home to roughly 3.4 million people. With its central location between the large estuarine known as the Puget Sound and another large body of water known as Lake Washington, it has served as a central hub for a lot of Seattle’s maritime industry for over 100 years. Before white settlers came along, the Duwamish Indians lived along the shorelines of Lake Union. They would hunt the nearby wooded areas and fish the lake from hollowed out cedar trees. In the 1800’s white settlers came and began to push out the natives. It was during the mid 1800’s when Thomas Mercer gave the Lake its current name of Lake Union. He correctly predicted that one day the lake would be a union of waters joining the Puget Sound and Lake Washington. From the 1800’s on, the lake has seen many changes including lakeside lumber mills and gas plants that are now public parks, an elevated vehicle trestle along the edge of the lake that is now a smoothly paved roadway, and canals that lowered the level of the lake by 9 feet. Many of the |

|

old structures that dot the shorelines of Lake Union have been transformed from naval buildings to museums and from power plants to sophisticated bioengineering firms. Despite the transformation that has occurred topside over the years, below the surface, Lake Union has kept its aging fleet of wreckage hidden from human eyes that travel the lake on a daily basis.

With its roughly 580 acres of surface area, the lake is popular among people engaging in activities such as kayaking, rowing, and boating due to its beautiful topside scenery. It is also a water- based runway for Seaplanes flying in and out of the Seattle area and a mainstay for many types of commercial vessels that use the lake for moorage and repair. With so much traffic utilizing the surface of Lake Union, diving is strictly prohibited by the harbor patrol. The only exception that has been made is for a group of divers who have been working with the Department of Natural Resources and Center for Wooden Boats to explore and document the wrecks that litter the bottom of Lake Union. With its roughly 580 acres of surface area, the lake is popular among people engaging in activities such as kayaking, rowing, and boating due to its beautiful topside scenery. It is also a water- based runway for Seaplanes flying in and out of the Seattle area and a mainstay for many types of commercial vessels that use the lake for moorage and repair. With so much traffic utilizing the surface of Lake Union, diving is strictly prohibited by the harbor patrol. The only exception that has been made is for a group of divers who have been working with the Department of Natural Resources and Center for Wooden Boats to explore and document the wrecks that litter the bottom of Lake Union.

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

The hearty divers spearheading the Lake Union archeology project are from a non-profit group called the Maritime Documentation Society. At least once a week, Chris Borgen, Erik Foreman, and Dan Warter can be found meeting along the shores of Lake Union, gearing up in closed-circuit rebreathers searching for a “new” wreck. About half of the wrecks have been located with the help of side-scan imagery, while the other half have been found during hours and hours of combing the bottom of the lake. When these divers discover a wreck, they first look for any identifying markings such as a name or any hull numbers. Then they document all measurements of the wreck followed up by taking video and photos. It’s only after doing all this, that they can peruse the archives for any leads to identifying the wreck and telling its story. In all over 30 wrecks have been discovered and documented in the past 3 years. The wrecks they have discovered have ranged from small wooden sloops to large WWII minesweepers, and everything in between. Until now, the historical background and significance of Lake Union had stopped at its surface. Below the surface, the other half of the story continues. The hearty divers spearheading the Lake Union archeology project are from a non-profit group called the Maritime Documentation Society. At least once a week, Chris Borgen, Erik Foreman, and Dan Warter can be found meeting along the shores of Lake Union, gearing up in closed-circuit rebreathers searching for a “new” wreck. About half of the wrecks have been located with the help of side-scan imagery, while the other half have been found during hours and hours of combing the bottom of the lake. When these divers discover a wreck, they first look for any identifying markings such as a name or any hull numbers. Then they document all measurements of the wreck followed up by taking video and photos. It’s only after doing all this, that they can peruse the archives for any leads to identifying the wreck and telling its story. In all over 30 wrecks have been discovered and documented in the past 3 years. The wrecks they have discovered have ranged from small wooden sloops to large WWII minesweepers, and everything in between. Until now, the historical background and significance of Lake Union had stopped at its surface. Below the surface, the other half of the story continues. |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| Photo: Wreck diver Erik Foreman points out one of the human hazards of diving in Lake Union. |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

Photo Examining the bow of a yet another unidentified wooden vessel. |

|

Diving the wrecks in Lake Union is always an adventure to say the least. Because most of the shoreline is occupied by large buildings, moorage, or houseboats, finding an entry point is always a task in itself. This also creates a semi-overhead type of environment because buildings were built out over the water, or boats are moored tightly together not allowing a direct ascent to the surface. The lake has seen over 100 years of industry and for most of those years all sorts of waste including paints, garbage, scrap metal, and anything else someone didn’t want to pay to get rid of was dumped into the lake. Not to mention it is a small lake with heavy boat traffic, and during the rain storms Seattle is so well known for, there are all sorts of oil and gas pollutants that seem to find their way into the water where they collect in the bottom sediment. Even with all these drawbacks, the team of explorers continues their search. Diving the wrecks in Lake Union is always an adventure to say the least. Because most of the shoreline is occupied by large buildings, moorage, or houseboats, finding an entry point is always a task in itself. This also creates a semi-overhead type of environment because buildings were built out over the water, or boats are moored tightly together not allowing a direct ascent to the surface. The lake has seen over 100 years of industry and for most of those years all sorts of waste including paints, garbage, scrap metal, and anything else someone didn’t want to pay to get rid of was dumped into the lake. Not to mention it is a small lake with heavy boat traffic, and during the rain storms Seattle is so well known for, there are all sorts of oil and gas pollutants that seem to find their way into the water where they collect in the bottom sediment. Even with all these drawbacks, the team of explorers continues their search.

Kahlenberg

Built in 1913, the 50 foot long 11 foot wide Kahlenberg was first used in the US Navy (believed to be during WWI) as a tender in Oriental waters, the gun mount was a prominent feature on the bow. It was most likely used to transport troops, equipment, ammunition, mail, food and supplies between fleets. The small wooden ship was eventually struck from the naval register and sold to private parties. Kahlenberg Industries Inc., well known to this day for their fishing and towboat engines, proudly used the small ex-naval tender vessel as their demonstration boat for their powerful new engines following the war. Built in 1913, the 50 foot long 11 foot wide Kahlenberg was first used in the US Navy (believed to be during WWI) as a tender in Oriental waters, the gun mount was a prominent feature on the bow. It was most likely used to transport troops, equipment, ammunition, mail, food and supplies between fleets. The small wooden ship was eventually struck from the naval register and sold to private parties. Kahlenberg Industries Inc., well known to this day for their fishing and towboat engines, proudly used the small ex-naval tender vessel as their demonstration boat for their powerful new engines following the war.

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

Photo: Diver points out a rusty propeller blade emerging through the silt of the “4s and 6s” wreck.

|

|

|

| |

| |

Impressed no doubt by her history, and power in a small package was a man named Captain France (Franz) Nelson. Purchased in Alaska by Nelson, the former tugboat Captain had plans to bring her to the Puget Sound and try his hand at the shrimping trade. Commercial shrimping was getting very popular in the Puget Sound, especially in Elliot Bay where deep shipwrecks made safe havens for the premium priced prawns. The local fisherman hovered over at least 6 well known wreck sites to catch their bountiful hoard. The Kahlenberg was one of the numerous shrimp boats swarming around the busy waterfront. The drag net on the Kahlenberg’s wooden stern was 15 feet wide, 25 feet long and attached to 600 feet of cable, all controlled by a winch powered by a 25 hp steam engine and Scotch boiler. The Kahlenberg’s average haul would be 30 minutes and she would cover a quarter of a mile, depending on the wind and tide. The net would reach depths from 180 to 300 feet deep. Franz operated the Kahlenberg for years making quite a name for himself and his small little boat. With only his wife Elsie and sometimes his son Bill acting as crew, they received quite a bit of notoriety. Impressed no doubt by her history, and power in a small package was a man named Captain France (Franz) Nelson. Purchased in Alaska by Nelson, the former tugboat Captain had plans to bring her to the Puget Sound and try his hand at the shrimping trade. Commercial shrimping was getting very popular in the Puget Sound, especially in Elliot Bay where deep shipwrecks made safe havens for the premium priced prawns. The local fisherman hovered over at least 6 well known wreck sites to catch their bountiful hoard. The Kahlenberg was one of the numerous shrimp boats swarming around the busy waterfront. The drag net on the Kahlenberg’s wooden stern was 15 feet wide, 25 feet long and attached to 600 feet of cable, all controlled by a winch powered by a 25 hp steam engine and Scotch boiler. The Kahlenberg’s average haul would be 30 minutes and she would cover a quarter of a mile, depending on the wind and tide. The net would reach depths from 180 to 300 feet deep. Franz operated the Kahlenberg for years making quite a name for himself and his small little boat. With only his wife Elsie and sometimes his son Bill acting as crew, they received quite a bit of notoriety.

The Seattle Times did a piece on his sturdy little vessel, and even Ivar Haglund (Ivars Seafood) came on board to examine the catch; no doubt wanting the best for himself. During one such encounter, the Kahlenberg pulled up more than just shrimp; a 60 lb. octopus and Haglund stepped into action. Making a quick decision, the Captain steamed the Kahlenberg over to the Seattle Aquarium on Pier 3, and Haglund carefully brought in the invertebrate. It’s unknown when the Nelsons parted ways with the last surviving vessel of the once bustling Elliot Bay shrimp fishing fleet. The Seattle Times did a piece on his sturdy little vessel, and even Ivar Haglund (Ivars Seafood) came on board to examine the catch; no doubt wanting the best for himself. During one such encounter, the Kahlenberg pulled up more than just shrimp; a 60 lb. octopus and Haglund stepped into action. Making a quick decision, the Captain steamed the Kahlenberg over to the Seattle Aquarium on Pier 3, and Haglund carefully brought in the invertebrate. It’s unknown when the Nelsons parted ways with the last surviving vessel of the once bustling Elliot Bay shrimp fishing fleet.

|

|

|

| |

| Photo: Erik posses beside the upside-down wheelhouse of the Navy Patrol Craft 1138. A sullen reminder of Lake Union’s connection with the past war efforts. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

J.E. Boyden

The Wooden tug J.E. Boyden was built near Bell Street in North Seattle in 1888 by a Norwegian shipbuilder by the name of T.W. Lake. The Boyden measured 85 feet 4 inches long, had a 19 foot beam, and bellied a 9 foot 8 inch hold. She was powered by a 2 cylinder compound 37NHP made by Washington Iron Works in Seattle, WA. Built for Captain T.A. Jensen, the Boyden was slated to join the Seattle fleet of steamers, Delta, E.W. Purdy, Halys, and Jayhawker, as well as the newly launched ferry boat City of Seattle. The Wooden tug J.E. Boyden was built near Bell Street in North Seattle in 1888 by a Norwegian shipbuilder by the name of T.W. Lake. The Boyden measured 85 feet 4 inches long, had a 19 foot beam, and bellied a 9 foot 8 inch hold. She was powered by a 2 cylinder compound 37NHP made by Washington Iron Works in Seattle, WA. Built for Captain T.A. Jensen, the Boyden was slated to join the Seattle fleet of steamers, Delta, E.W. Purdy, Halys, and Jayhawker, as well as the newly launched ferry boat City of Seattle.

The year 1890 brought about a dramatic change in steam boating on Puget Sound. With the rise of coal being extracted from nearby areas, Puget Sound steamers and tugs stepped up to move this new precious resource. A million dollars worth of steamers is said to have been brought to the Sound’s emerald waters, and with it, Seattle’s supremacy as the commercial hub of Puget Sound. In 1896 the J.E. Boyden was involved in a large scale attempt to free a stranded square rigger, the British iron ship Kilbrannan. On February 4th the Kilbrannan, a deepwater sailing vessel, attempted entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca without the assistance of a tugboat. Deciding to go ahead and brave the currents, she entered the Strait before a westerly breeze. Upon coming abeam of Race Rocks, the breeze turned into a full gale. Adding to the danger of the gale, she came along Point Wilson and was hit with very strong ebb currents which for several minutes held the iron bark abeam of the point. When there was a lull in the strong wind, the Kilbrannan was sent slowly astern. The year 1890 brought about a dramatic change in steam boating on Puget Sound. With the rise of coal being extracted from nearby areas, Puget Sound steamers and tugs stepped up to move this new precious resource. A million dollars worth of steamers is said to have been brought to the Sound’s emerald waters, and with it, Seattle’s supremacy as the commercial hub of Puget Sound. In 1896 the J.E. Boyden was involved in a large scale attempt to free a stranded square rigger, the British iron ship Kilbrannan. On February 4th the Kilbrannan, a deepwater sailing vessel, attempted entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca without the assistance of a tugboat. Deciding to go ahead and brave the currents, she entered the Strait before a westerly breeze. Upon coming abeam of Race Rocks, the breeze turned into a full gale. Adding to the danger of the gale, she came along Point Wilson and was hit with very strong ebb currents which for several minutes held the iron bark abeam of the point. When there was a lull in the strong wind, the Kilbrannan was sent slowly astern.

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

Photo: Not just derelict vessels litter the bottom of Lake Union, this is a 50’s era Dodge that rests upside-down in the muddy bottom. |

|

| |

| |

Photo: Photographer Chris Borgen shoots a photo of Erik posing beside the bow of the long-line trawler “Jeanette”. |

| |

|

|

A little before 2:30 am on February 5th, the large ship was forced into the eddy off the north side of the point, and drifted broadside onto the beach. The tide was ebbing, and the Kilbrannan was left alone high and dry on the beach. The next day the sea going tugs Tyee, Sea Lion, Richard Holyoke, Pioneer, and the powerful J.E. Boyden all combined forces at high tide to try and free the beached hulk. This went on for months, but to no avail. Finally a channel was dug, and she was set free of her hold, and towed back to Esquimalt dry dock. A little before 2:30 am on February 5th, the large ship was forced into the eddy off the north side of the point, and drifted broadside onto the beach. The tide was ebbing, and the Kilbrannan was left alone high and dry on the beach. The next day the sea going tugs Tyee, Sea Lion, Richard Holyoke, Pioneer, and the powerful J.E. Boyden all combined forces at high tide to try and free the beached hulk. This went on for months, but to no avail. Finally a channel was dug, and she was set free of her hold, and towed back to Esquimalt dry dock.

1906 brought change to the habitualness of the J.E. Boyden’s exceptional service to northwest Washington. Mackenzie Brothers Ltd. in Vancouver British Columbia bought the tug to join their fleet in the hauling of ore and coke (solid residue from roasting coal in a coke oven) from Union Bay, Seattle and other coastal ports. 1906 brought change to the habitualness of the J.E. Boyden’s exceptional service to northwest Washington. Mackenzie Brothers Ltd. in Vancouver British Columbia bought the tug to join their fleet in the hauling of ore and coke (solid residue from roasting coal in a coke oven) from Union Bay, Seattle and other coastal ports.

Later as shipments increased and with the Mackenzie Bros. transporting everything from copper ore to livestock, they needed more power and more deck space. Later as shipments increased and with the Mackenzie Bros. transporting everything from copper ore to livestock, they needed more power and more deck space.

The Georgian II, a large tow barge was modified structurally in the way of overall strengthening, the construction of additional trusses and further arching of the deck. Two additional compartments were also added for livestock. Another large barge, the Canada, was further added to the quickly increasing fleet.

When the Boyden was purchased for service in 1906 it was one of these barges it routinely towed. Usually engaged in the ore trade, the Boyden would also tow the barges full of lumber and coal between ports on Vancouver Island and the lower mainland. In addition to the J.E. Boyden being deep in the commodities trade, it was likewise often chartered to move rail cars from Ladysmith to Vancouver for the Canadian Pacific Railway. |

|

|

| |

\

| |

|

| Photo: Yet another one of the many derelict vessels that lies undisturbed under the bustling surface of Lake Union’s dry docks. |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

Photo:: So much has sank or been discarded in Lake Union that wrecks lay on top of other wrecks. Excavation of multiple layers would need to be conducted to discover what lies below. |

|

Being used for just about anything that could pay to keep her burning, the Mackenzie Brothers sought work for her towing log booms from Vancouver Island and up-coast logging camps to lower mainland sawmills. Considered one of the most efficient log towing masters of the world, E.F.Bucklin, piloted the J.E. Boyden, and it was said that in his 45 years of towing, he never lost a boom of logs.

The Boyden remained in service for the Mackenzie Brothers until 1908 when it was sold to Boyden Tug Boat Co. Ltd. In Victoria, British Columbia.

In 1921 the Boyden was sold, once again, to the Pacific Tug Boat Company of Seattle, Washington. Here it remained in service until 1935 when it was stripped and abandoned, probably in the black stillness of night, to the middle of Lake Union where it was most likely quietly scuttled.

These are only two of the many wrecks these divers have explored and documented during the project. Many of the other notable wrecks include the YMS-105/Gypsy Queen, Jeanette, two separate WWII landing craft, the PC-1138, and many more. A lot of the wrecks that have been discovered are badly deteriorated making it almost impossible to identify, and in some place wrecks are stacked 3 high. We are still searching for some more historically significant wrecks including one of Boeing’s first planes that crash-landed into Lake Union in front of where founder William Boeing had built his airplane hangar.

For the divers working on the Lake Union archeological project, this experience has been eye-opening and given them a sense for the history in their own backyards. They have found many different things in the lake including turned-over cars, human remains, guns, and of course wrecks. As long as the project continues, you can be sure they will be there documenting and exposing the history behind the wrecks at the bottom of Lake Union. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|