|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No mere “Shark Week” could have prepared me for the overreaching immensity of my first carcharodon carcharias rising from below…3,000 pounds and 15 feet of shark nearing our titanium-reinforced aluminum cage. |

|

|

|

|

Text by C.J. Bahnsen

Photography by Shark Diver and Chris Limon

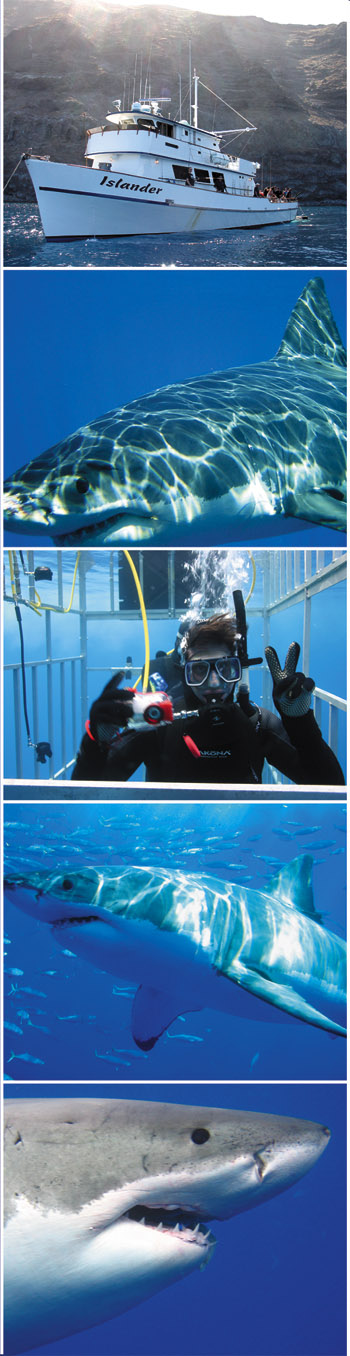

“Peter Benchley is on the Horizon,” our dive ops manager, Tracy Andrew, announced as she disembarked from the panga boat and climbed aboard our 85-foot charter dive vessel, the Ocean Odyssey. I was among the 16 shark divers and 10 crewmembers who stood bunched and excited on the afterdeck upon hearing the news. With overeager impatience, I asked, “Did you talk to him?”

It was November of 2004. Our vessel sat anchored in the northeast leeward side of Isle de Guadalupe, some 300 yards off an area known as “Shark Heaven.” The Horizon, sister boat of the Odyssey, was anchored not far off, also loaded with shark divers, led by eco tour operator, Paul “Doc” Anes. I was signed on with Patric Douglas, youthful swarthy-tanned CEO of Absolute Adventures-Shark Diver, for a five-day live-aboard package. Tracy had been tooling around on a panga with the shipboard shark researcher, Mauricio Hoyos Padilla, who was tracking acoustic transmitter signals from tagged sharks with a hydrophone. When they motored past the Horizon, there was Peter Benchley and his wife Wendy among the dive party. “We just waved a ‘Hello’ to him,” Tracy said to my disappointment.

Guadalupe breaks open the sea 160 miles offshore of Baja California Norte. Cinder cones, geological folds, and vermillion striations of lava rock are evidence of the island’s volcanic birthing. It is a rugged, 22-hour, stomach-churning steam for 220 miles due south from San Diego Harbor to get there. The bio-diverse island hosts an excess of big game fish, especially yellowfin tuna and yellowtail, which attracts sport fishermen. In 1998, long-range fishing boats out of San Diego began reporting great whites making shock-and-awe attacks on their catch. Word spread like chum.

Guadalupe represents an aqua Eden for shark divers. Unlike South Africa, Australia, and the Farallon Islands, visibility is often crystalline, well over 100 feet on the best days. Provided you chum the water, white sharks are almost guaranteed to show up everyday during the season.

It burned me that I was never able to get close enough to speak with Benchley during the four days we were both at Guadalupe, being that our vessels remained about 600 feet apart. So when I returned to my bungalow in Orange County, I sought him out via his publisher. A week later an errant email arrived from Benchley, inviting me to phone his East Coast residence on January 28, 2005.

“In South Africa, they do most of the cage diving off these monster seal colonies,” he told me, when I asked how his first trip to Guadalupe rated against other shark sites. “The sharks are all over you there, fifteen to twenty at a time in a given day. I’ve been to South Australia half a dozen times, and I’ve always had pretty bad luck there. On one trip, we saw only one shark in eight days. Guadalupe was certainly better than my experiences in Australia. There were more great whites there, and they were much less shy. To have about three or four sharks around the clock for four straight days was top of the scale.”

I also saw sharks regularly during those same days. Although Benchley and I were on separate boats under different eco-operators, the drill was essentially the same on the Odyssey and her sister vessel. Each one-hour dive rotation consisted of dropping into one of two 10' x 20' cages deployed over the stern, four divers per cage.

Unlike everyone else on the Odyssey, I was not a certified diver at the time. Non-certs are allowed on these dives since you don’t go below ten feet, and breathing is done with a hookah. Odyssey divers were each cinched in a 60-pound weight harness so we wouldn’t be bobbing around like loose corks. The water temp here averages 60-62 degrees during high shark season (September through early December), which constitutes coldwater diving. And because you’re standing immobile in a cage rather than swimming, your core body temp drops. “I don’t like coldwater diving,” said Benchley, who wore a 40-pound harness and considered the water temp “marginal for a wetsuit.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

On my first dive, I was bordering on sensory overload as I wrestled into a borrowed 7mm wetsuit, then the head-shrinking hood, boots, and gloves. The whole getup felt like a black python had me in a goodnight squeeze. There was so much to think about, like the rules Tracy had laid down at first dive meeting: “Never stick any part of your body outside the cage, and never make any sudden movements that might trigger a predator-prey reaction,” she admonished.

Tracy would monitor us from the dive platform. Another sharky would man a push-pole during rotations. “If a shark were to come in too close to the cages, we push it off,” Tracy said. “It doesn’t harm the shark. We just give them a little extra nudge to keep them from entering the cage, because sharks don’t have a reverse mode.”

Patric and crew had been tossing five-gallon buckets of tuna parts, hang bait, and powdered chum—made from dried fish and blood meal—over both gunwales. I thrust the reg in my mouth, threw my legs into the lurching cage, and KER-PLOOSH!

When the bubbles cleared, I was standing on the cage floor. I got tossed around a bit, trying to fight the currents until I realized the idea was to stay loose, knees bent in a boxer’s stance. Visibility was at 25 feet, well shy of the usual 80-plus feet. A plankton bloom was turning the blue water green and dusky, caused by deepwater upwelling that comes from the submarine canyons here.

Standing in the cage weighted to negative buoyancy felt like being on the moon at one-third gravity, only the hazy green cosmos was inverted, plunging between my neoprene boots, streaked by cornflower blues. Depths quickly nose-dive to over 1,300 feet moving out from the island.

We waited. Ten, twenty, thirty-five minutes went by. No sharks. Then I felt a shoulder tap, and Alan was pointing down to our left. At first I saw nothing; until part of the sea separated from itself, becoming a grey-green plasmatic specter that took on form. The preternatural girth of the animal—nine feet or so—reduced me to an awed simpleton.

No mere “Shark Week” could have prepared me for the overreaching immensity of my first carcharodon carcharias rising from below…3,000 pounds and 15 feet of shark nearing our titanium-reinforced aluminum cage. Solar vines shimmered off the great white’s back like lightning flashes as the titanic fish moved with eons of evolved efficiency. Even at first sighting, I knew the design could not be improved on. Not as a cruising killing machine.

|

|

|

|

|

Her beauty was so overwhelming as to take away my fear. At that moment, I understood why Benchley loved sharks and why—through conservation work, TV appearances, lectures, and nonfiction books like Shark Trouble—he spent the latter part of his life trying to defang the empire of terror he had created with Jaws, which he had meant as fiction, not as an excuse to go out and headhunt sharks.

The low viz, along with a great white’s notorious ability to change hues—different combinations of blue, silver, charcoal grey, sea green, and bronze—allowed the sharks to manifest like a haunting: near the surface a ways off one moment, right under the cage floor the next. The animals seemed to assemble from phantasmal mist, as if teleported from the deep. “It was very eerie,” Benchley said about this phenomenon. “You’d turn around and there would be one right there. Doc Anes, a real character who ran the operation, told us, ‘Remember, it isn’t the shark you see that’s going to get you, it’s the one you don’t see that does.’ “

Benchley nearly lived those words. “I had my hand out to touch a shark passing the cage. Well, there was another shark following close behind that I didn’t see at all. Had she wanted to, she could have easily had a hand or an arm for lunch,” he said.

It turned out the female great white that cage-stormed my team was “Scarboard,” named so because of the singular scars on her right flank. Scarboard is almost always observed with an escort school of pilot fish. She is one of over 70 adult and sub-adult great whites photo-documented in these waters by Pfleger Institute for Environmental Research (PIER), headquartered in Oceanside, California. Young male whites, averaging 11-14 feet, first appear in early July, while larger adult females begin showing up around September. The largest shark observed by scientists and eco tour operators was 16 feet, but local fishermen have reported sharks as large as 20 feet.

The great whites we saw averaged between 11 and 15 feet…until our last dive rotation on the third day as the yolky sun waned over Mount Augusta, Guadalupe’s razorback 4,257-foot peak. The sea had turned docile blue overnight as the winds died. We weren’t bullied by currents in the cage, and viz was 60 feet and improving. My consciousness was spilling into the big blue when a 14-foot female materialized from below the Odyssey’s hull. She passed close enough for a pectoral fin to rattle the cage bars. As she receded, another great white — also a female — eclipsed my mask window. She swam beneath the cage and ghosted away.

Both sharks were hidden, but you could feel them out there. Movement erupted from the starboard. The new shark was a giantess, moving under the panga boat that had returned with Mauricio, lingering alongside it. I would have rebuked her size as some freak underwater refraction, except her body ran the length of the panga. That would make her at least 18 feet, and about two tons. Mauricio, who observed the shark from above, corroborated this later.

The queen beast glided on pectoral wings, moving to the hang bait that floated just below the surface off starboard, mouth toward us as it yawned open. The upper lip crinkled back, revealing bloody gums then a bony ridge filled with layers of serrate teeth like broken razorblades. The cavernous passage to her gullet waited. She tore the bait from the line with an easy swipe of her head, and continued toward us fronting a slack-jawed grin. She moved in along the cage, taking a good look inside. Her right eye landed on me like a dual judgment from God and Old Scratch. I was looking into an omnipotent black hole that slung me back 11 million years.

Sharkdiver.com

RioFilms.com

SharkTrustWines.com

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|