|

| |

|

|

|

|

By Jitka Hyniova

|

|

|

|

he living fossil fish Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) is regarded as an extremely rare species. Only fossil records of Coelacanths were known until the famous discovery in 1938 in South Africa. The second fish was caught 53 years later in Mozambique, but thereafter more specimens have been caught off the coasts of the Comoros, Madagascar, Kenya, and recently Tanzania. he living fossil fish Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) is regarded as an extremely rare species. Only fossil records of Coelacanths were known until the famous discovery in 1938 in South Africa. The second fish was caught 53 years later in Mozambique, but thereafter more specimens have been caught off the coasts of the Comoros, Madagascar, Kenya, and recently Tanzania.

Underwater studies off the coast of South Africa, using submersible vessels, revealed that Coelacanths inhabit submarine caves and canyons found in slopes and walls in waters 100-700 meters deep. The adult Coelacanths can grow to about 1.5 meter long. They appear to be active at night, spending their day hovering near the ocean bottom. Scientists believe that Coelacanths can live as long as 80 years.

My obsession with this bizarre lobefin fish started in the early 1980s while reading an article about its fascinating first discovery, and the decades-long quest to find more specimens. Little did I know that after more than 20 years, I would actually get to see the ancient fish as a member of a deep diving expedition off the coast of Tanzania.

In May 2006, after almost a year of preparations, hours spent library and Internet crawling, I was finally seated on a transatlantic flight heading to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. I didn’t mind checking in with excessive baggage since my bulging expedition boxes contained my Megalodon closed circuit rebreather, dry suit, powerful underwater lights, reels and lift bags, and everything one can need on a far away deep diving expedition. My luggage also contained housing for my video camera, a still camera, and the few pieces of clothing needed to maintain decency in the foreign and fairly conservative land.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Above: Coelacanth habitat near Kigombe as captured by the Kairos sonar. The Indian Ocean bottom in that area falls rapidly from 90m (297ft) to 150m+ (500ft+). Photo: Jitka Hyniova. |

|

|

|

|

With the numerous small islands and shallow reefs stretching as far I could see from 10 km high in the air over the coastline of Kenya and Tanzania, thoughts of unexplored wrecks crossed my mind. But my goal this time would be looking for something totally different – the Coelacanth fish!

Shortly after landing in Dar es Salaam, I passed the strict looking but very welcoming Tanzanian custom and immigration officers, and was greeted on the sidewalk by Monsieur Thierry Thevenet, the owner of The Kairos Company, and his land-based Tanzanian associate and driver, Pierre.

The Ship

Out of Dar es Salaam, The Kairos Company operates their 36-meter (119 foot) state-of-the-art ship, which is not only comfortable but is literally a floating oceanographic laboratory and ideal diving platform. The Kairos was originally built in Germany to spy on Russia during the Cold War.

One of the newest and most impressive tools aboard Kairos, and one that every deep diver will appreciate, is the two-man hyperbaric chamber on deck. Along with Thierry, I had the privilege of helping to install and test the newly acquired chamber, under the supervision of French hyperbaric specialist and another member of our expedition – Dr. Andre Grousset.

|

|

|

|

|

Right: Expediton divers from left to right: author Jitka Hyniova, Dr. Andre Grousset and TD Van Niekerk. Photo: Catherine Dulin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Kairos is equipped with two support chase boats, three cranes, compressor, Nitrox filtration system, scooters, and multiple Dolphin SCRs. For those hard to impress, they even have microlite aircraft that can be used for spotting whales, sharks, and for breathtaking aerial photography! Since our goal was to dive deep, the Kairos provided helium, oxygen, and scrubber material for our rebreathers.

The visiting photographers and filmmakers will appreciate the fully equipped editing suite, including a large plasma monitor for immediate viewing of their daily work.

The Kairos holds 60 tons of fresh water and 40 tons of fuel. The comfort of the passengers is complemented by genuine French cuisine; the ship’s French captain personally supervises the menu! Speak of the five star meal presentation!!!

The Kairos is usually hired by various scientific and exploration projects with some spaces open for divers interested in serious expeditions. Also, several renowned underwater photographers come back repeatedly to work in the beautiful and unique waters of the Tanzanian coastline.

The Search

Our expedition wouldn’t have been possible without Tanzanian scientific support, and we were lucky to be joined by Mr. Shelard Mukama from the University of Tanzania in Dar es Salaam. Mr. Mukama works directly on Coelacanth research and conservation, and was crucial for his firsthand knowledge of recent Coelacanth sightings and as a contact with local authorities and fishermen. Based on Mr. Mukama’s information, we started by visiting the small fishing village of Kigombe, a day of sailing north of Dar es Salaam. We paid an official visit to the local fisheries office based in a small hut. We were greeted very warmly, and after signing our names in the guest book, our small delegation of divers was seated in hardwood straight-backed chairs facing the committee of Kigombe fishermen.

With Mr. Mukama acting as translator, we were able to borrow one fisherman for a day and take him aboard Kairos. Contrary to his slim and rather short physique, Said had recently caught and brought to the surface a 60kg (132 lb) Coelacanth fish — more than he weighs himself! The Coelacanth is really an unwanted bycatch – the fish is supposedly oily and of little market value. Kigombe fishermen use very narrow two-man dugout canoes, with weighted lines to catch grouper, snapper, tuna, sharks, etc. They bring nothing in their canoes but their fishing license hanging in a small plastic bag on their sun-bleached hats.

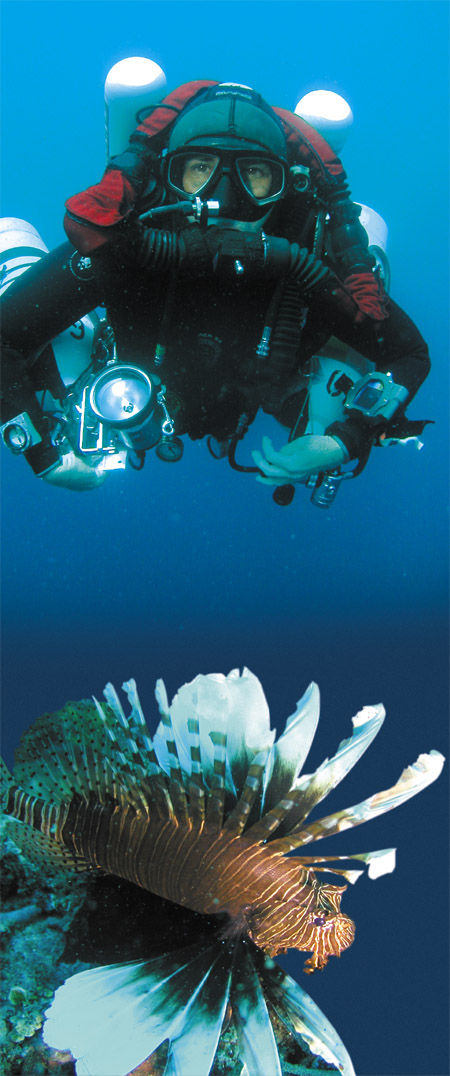

Left: Tanzanian waters are tropical fish paradise and Lionfish is Indian Ocean’s native. Photo: Matt Matthes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

While the dive team was visiting the village, the Kairos crew was busy sailing along the coast and surveying the ocean bottom with the ship’s sonar looking for deep walls with canyons and caves that Coelacanths use as their habitat. Despite having virtually no modern navigation systems (forget GPS), the Kigombe fishermen know their way along the coast. Said’s location of ideal Coelacanth habitat was indeed confirmed by the ship’s sonar, and also by water temperature sensors. Coelacanths prefer cooler deep water to very warm shallower water, and our temperature sensors indicated a thermocline at 90 meters.

The Diving

Based on our support system, the divers agreed on the necessity of diving as a four-man team and covering as much ground as possible. The currents in that part of the Indian Ocean are known to be treacherous with multiple changes in directions over depth. We were also well aware of the big sharks known to hang out in these waters — as well as the fact that the nearest medical help is days away. We utilized a chase boat; but with closed circuit rebreathers and no bubbles in sight, the spotter’s role becomes difficult. CCR divers on deep two-hour long dives can travel some distance carried by the ocean currents. For safety and comfort during long decompression, we built and used a deco ladder hanging beneath our chase boat and loaded with extra decompression gas. Matt Matthes of ProTec Mexico was brilliant in his function as our Diving Safety Officer. He was able to moderate the often bilingual discussions about gases, decompression, and bailout strategies by divers from three different continents and a variety of technical diving backgrounds.

Our Classic Inspirations and Cave Megalodons performed flawlessly, and we dove on two different Coelacanth locations to 97m (320fsw) and 124m (409fsw), respectively. We did encounter perfect conditions, the currents were mild after all, and the thermocline was exactly where expected at 90m (297fsw). At 18C (70F), the deep-water temperature was ideal for Coelacanth habitat. We captured on HDV camera the deep caves and canyons described in literature as favored by Coelacanths. At 100 meters, we still had enough daylight to observe deep-water gorgonians and huge sponges — but it was not our time to see the Coelacanth fish yet!

Top: TD Van Niekerk after surfacing from video dive where he filmed the deep canyons assumed to be Coelacanth habitat. Photo: Matt Matthes.

Middle: The Kairos ship is equipped with two men hyperbaric chamber and our team ran drills to test it’s operation. Photo: Jitka Hyniova.

Bottom: Dr. Andre Grousset is getting ready to dive and hopefully see the Coelacanth fish in it’s habitat. Photo: Catherine Dulin. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To our great disappointment, and after only two days of deep diving, the hyperbaric chamber’s high-pressure feed hose unexpectedly broke while standing by. The consensus on board was not to continue with the deep diving until we could get a replacement.

Nevertheless, we spent the following several days diving shallow but beautiful and absolutely pristine coral reefs around the island of Pemba and near the northern Tanzanian coast. The amount and diversity of marine life was amazing, and the Kairos was the only dive boat in the area.

While we anchored in the port of Tanga, some of the divers and crew got to the shore to visit the local Internet café. I didn’t want to give up my search for Coelacanth. I talked Mr. Mukama into helping me find what I hoped could fulfill my dream of seeing the ancient fish. The Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme resides in a picturesque historical building on the main street in Tanga just 10 minutes from the port. We were lucky to get there just before the offices closed; after a brief introduction of our team and goals, we were taken to a small back room with a large freezer. And there was the fish. Not one but three Coelacanths ranging from 60 to 120 kilograms, deep-frozen on top of each other. It is not every day that you come face to face with a “dinosaur” dating back 400 million years. As we took pictures of the fish, I felt strangely sad for not being able to see the fish in its natural beauty and alive.

Coelacanths are not targeted by local fishermen; but, when caught as bycatch, they can be used for educational and research purposes. The Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme was established to help reduce some destructive fishing practices and, while working with the local fishermen, to monitor and manage Tangan coastal resources. They are interested in collaborating with research institutions, and getting some of the bycatch Coelacanths into exhibits and museums around the world.

The Kairos Company continues to work together with Tanzanian scientists and fishermen and interested divers from all over the world, and to organize another Coelacanth expedition in the spring of 2007.

The 2006 Coelacanth Expedition team: Thierry Thevenet, Jean Francois Arnefaux, Andre Grousset, Pascal Chauviere, Phung Truong, Catherine Dulin, Magali Assaly (all France), Matt Matthes (Mexico), TD Van Niekerk and Jitka Hyniova (Florida), and Shelard Mukama (Tanzania).

To get to know more about The Kairos, its expeditions and programs, and how to participate, visit them at

www.thekairoscompany.com |

|

|

|

Below: The Coelacanth 2006 Expedition multinational team, from left:

Pascal Chauviere, Shelard Mukama,

Matt Matthes, Thierry Thevenet,

TD Van Niekerk, Jitka Hyniova and

Dr. Andre Grousset.

Photo: Catherine Dulin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|